Taking Measures

Usages of Formats in Film and Video Art

The international video symposium fosters a dialog between art and research. Filmmakers, artists, researchers and scholars enter into creative and experimental conversation with each other about the usages and understandings of formats in film and video art.

The focus is placed on artistic media and practices in which the technologies and ideologies of measurement, their many validity claims and areas of application are addressed. The title of the symposium—“Taking Measures”—should be understood in its double meaning: as a reference to the practices of measurement related to the use of artistic media as well as to the political potential of power and resistance that results from these practices.

“Taking Measures” should be understood in its double meaning: as a reference to the practices of measurement as well as to the political potential of power and resistance that results from these practices.

Artistic media are subject to various practices of measurement. They are described and evaluated according to their size and proportions, depth and width, length and duration, rhythm and timing, etc. These categories are aesthetic, but they are also effective in a social and political sense, as they subject the use of artistic media to certain conditions of production and distribution. It is here that format as a decisive category comes into play.

The designation of film formats such as 35mm, 16mm, or 8mm, for example, is determined by the width of the filmstrip, which in turn corresponds to the size and aspect ratio of the single frames, as well as the duration of the film projection at a given frame rate. Magnetic video tape formats such as U-matic, Betamax, and VHS, or digital media formats such as floppy disc, CD-ROM and DVD are differentiated according to their image resolution, running time and storage capacity. As units or ensembles of technical specifications, formats are the result of historic processes of industrial standardization that are subject to the laws of uniformity and profitability. Format standards guarantee technical compatibility as well as economic competitiveness on the global image market. They determine not only the technical conditions under which media operate, but also where and by whom they are seen, the speed at which they circulate, the channels through which they are disseminated, and how visible and effective they are. Thus, formats determine the conditions under which images come to be publicly accessible and valued in a social and political regard in the first place.

Formats determine the conditions under which images come to be publicly accessible and valued in a social and political regard.

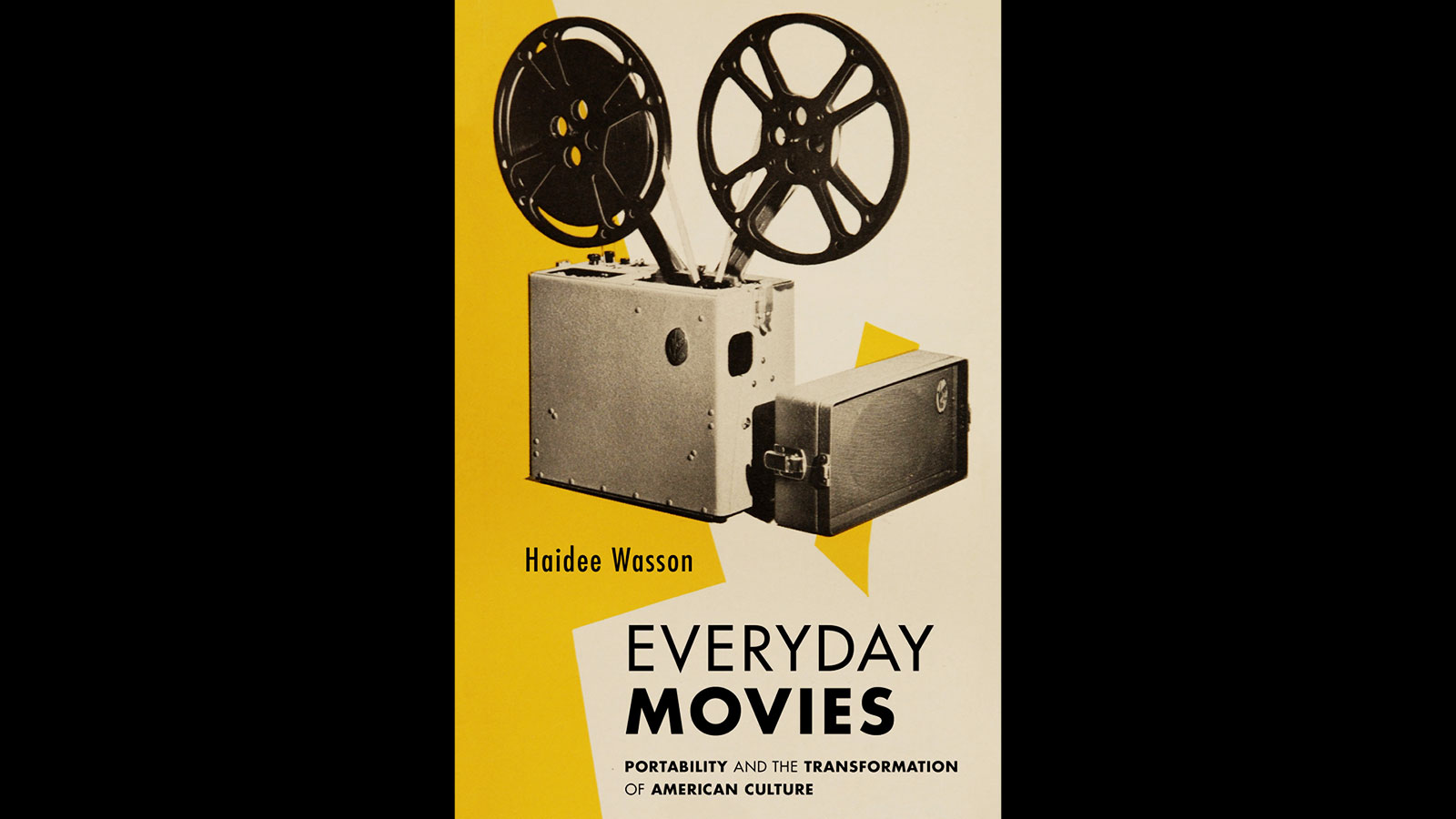

In view of its significance for artistic and curatorial practices, the format as a theoretical concept has recently become the focus of increased attention. Despite the significant differences between the approaches of David Summers, David Joselit, Jonathan Sterne, Haidee Wasson, Benoît Turquety and others, they share a common objective, namely to address the contexts of the use of formats in specific historical situations. The focus lies on artistic practice “after art,” on the multiple dependencies of artistic production, its technologies, and methods on political and economic interests. In this regard, David Joselit speaks about format as a structure or a “connective tissue,” wherein the worldly entanglements of images—the techniques of their production, the efforts associated with their creation, the mode of their circulation, the historical conditions of their making, etc.—become visible.

Film and video have served as measuring instruments for scientific and analytical purposes in a variety of fields. In acknowledging these dependencies also lies the opportunity for art to test its own effectiveness in the public arena and to uncover potential for resistance in artistic action.

The techniques of measuring time and space that have accompanied film and video throughout their history to the present day are subject to various processes of negotiation in the interest of science and politics, industry and commerce. Consequently, film and video have themselves served as measuring instruments for scientific and analytical purposes, whereby they are employed beyond exhibition spaces and movie theaters in a variety of fields such as anthropometry, criminology, biometrics, forensics, statistics, robotics, operations research, and tactical analysis in sports and military intelligence, respectively. In these fields, they contributed to the acquisition of knowledge, to research and investigation to the same extent as they were involved in the “politics of large numbers” (Alain Desrosières) and the history of the “mismeasure of man” (Stephen Jay Gould)—in the governmentally and ideologically motivated production of evidence through the collection and management of useful data. However, in acknowledging these dependencies, in view of which art jeopardizes its autonomy, also lies the opportunity for art to test its own effectiveness in the public arena and to uncover potential for resistance in artistic action. Formats indeed regulate the use of artistic media, in so far as they are scripts that contain guidelines for action through which historical knowledge and experience are accessed and distributed. At the same time, however, they are a showplace for negotiating, verifying, or dismissing the knowledge and experience they make available in standardized form.

Formats are scripts that contain guidelines for action through which historical knowledge and experience are accessed and distributed. At the same time, they are a showplace for negotiating, verifying, or dismissing the knowledge and experience they make available in standardized form.

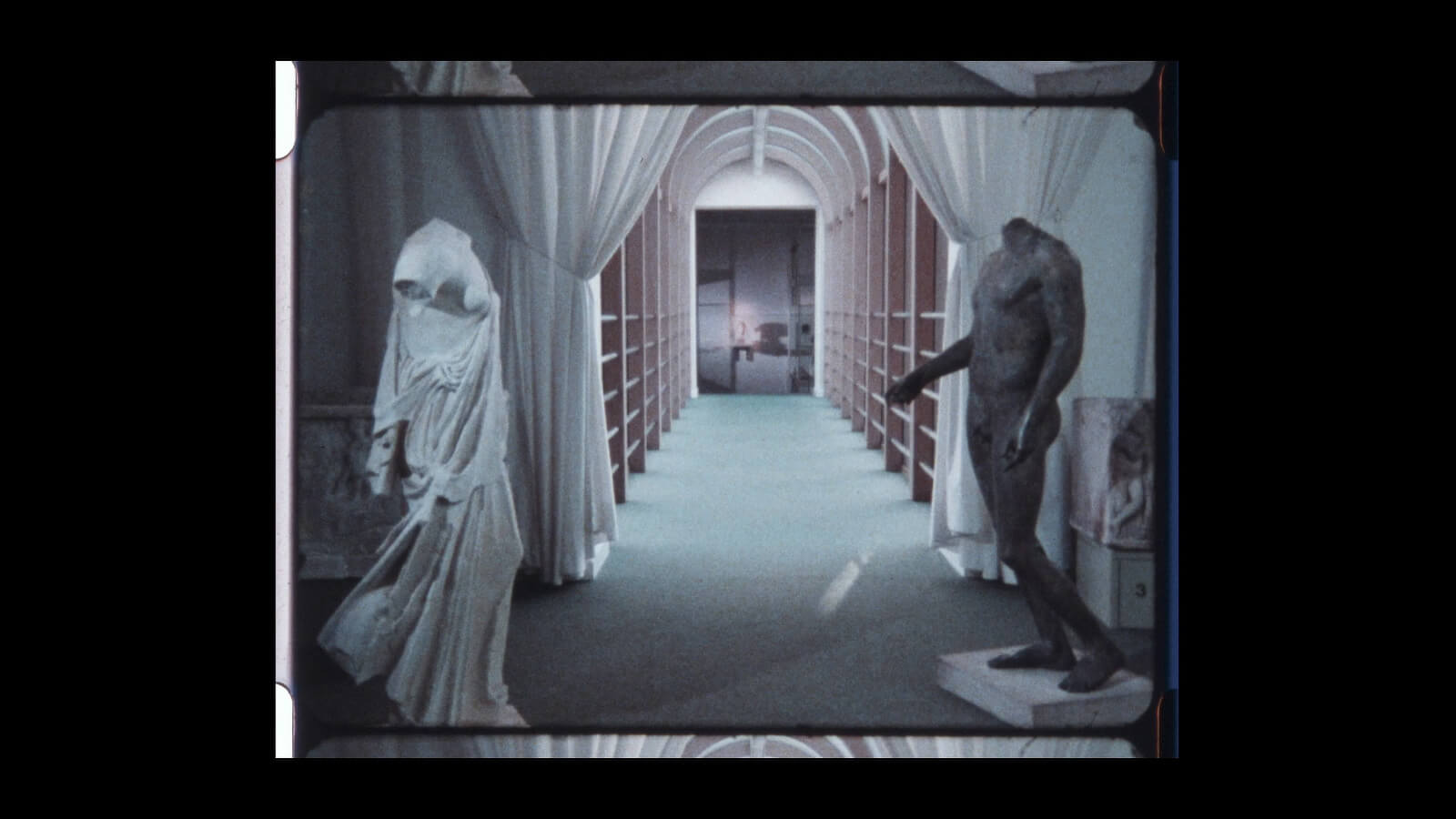

And finally, formats represent a particular challenge in the conservation and curation of collections. On the one hand, in addition to the works of media art that exist in obsolete formats, the technological systems and devices on which they can be played must also be preserved and kept in working order. On the other hand, the question arises as to the conditions under which these works should be converted into current digital formats to ensure that they can be exhibited in the future and possibly to retain a work’s original artistic concept—or even to realize this concept for the first time in situations in which it was impossible under the prevailing historical technological conditions. Conversely, conscious artistic recourse to “retrograde technicity” (Gabriele Jutz) can also be considered an act of undercutting technological standards, which is associated with subversive modes of format usage. Formats can circulate between the areas of normative and alternative usage or can be recontextualized through acts of appropriation and translation. At the same time, along with the artistic decision in favor of a certain format, the institutional practices that decide whether films and videos can be exhibited in the different contexts of museums and movie theaters as well as on television and the internet also come into focus.

Out of these considerations, a variety of questions arise that are addressed in the contributions to this video symposium:

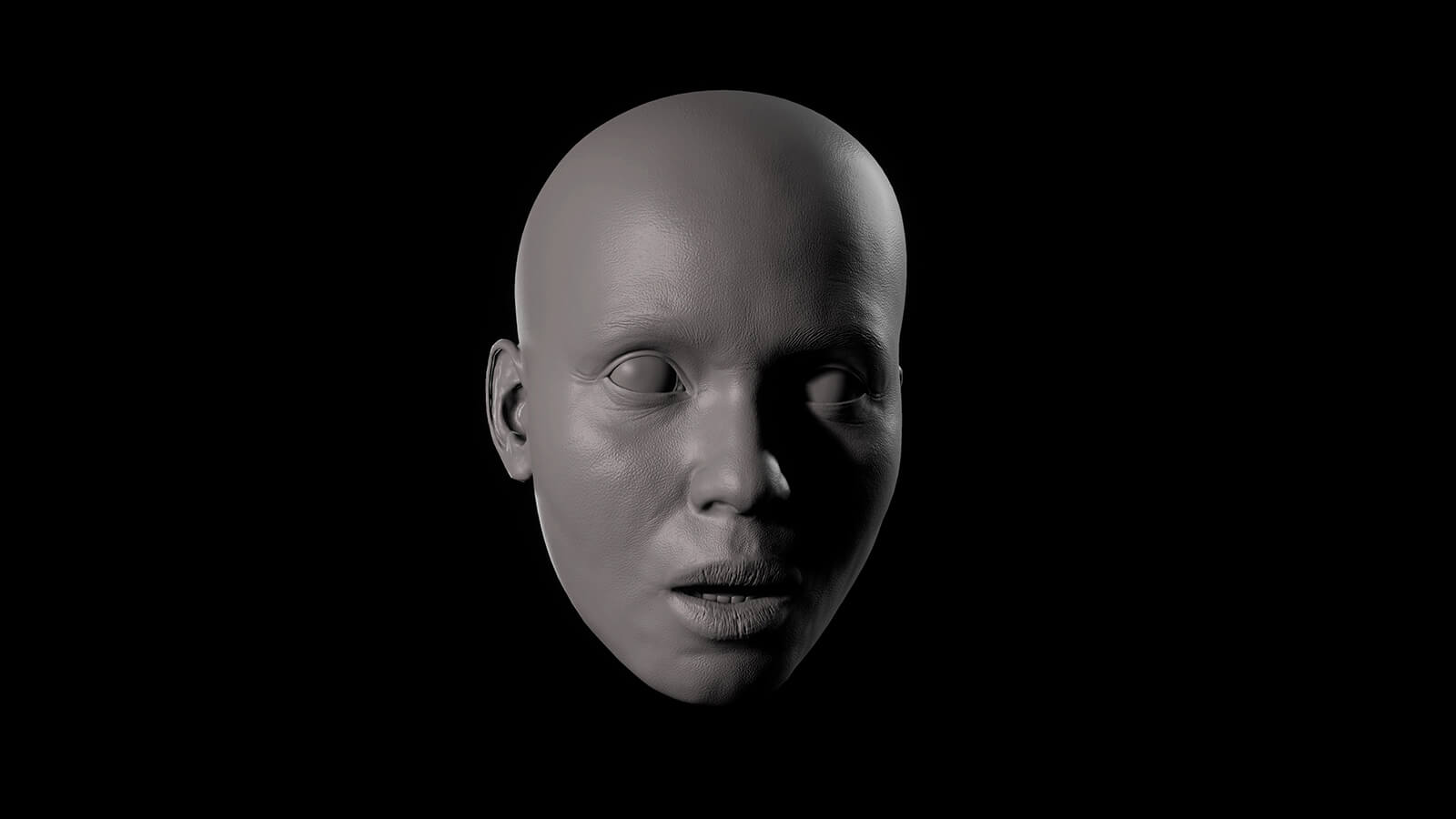

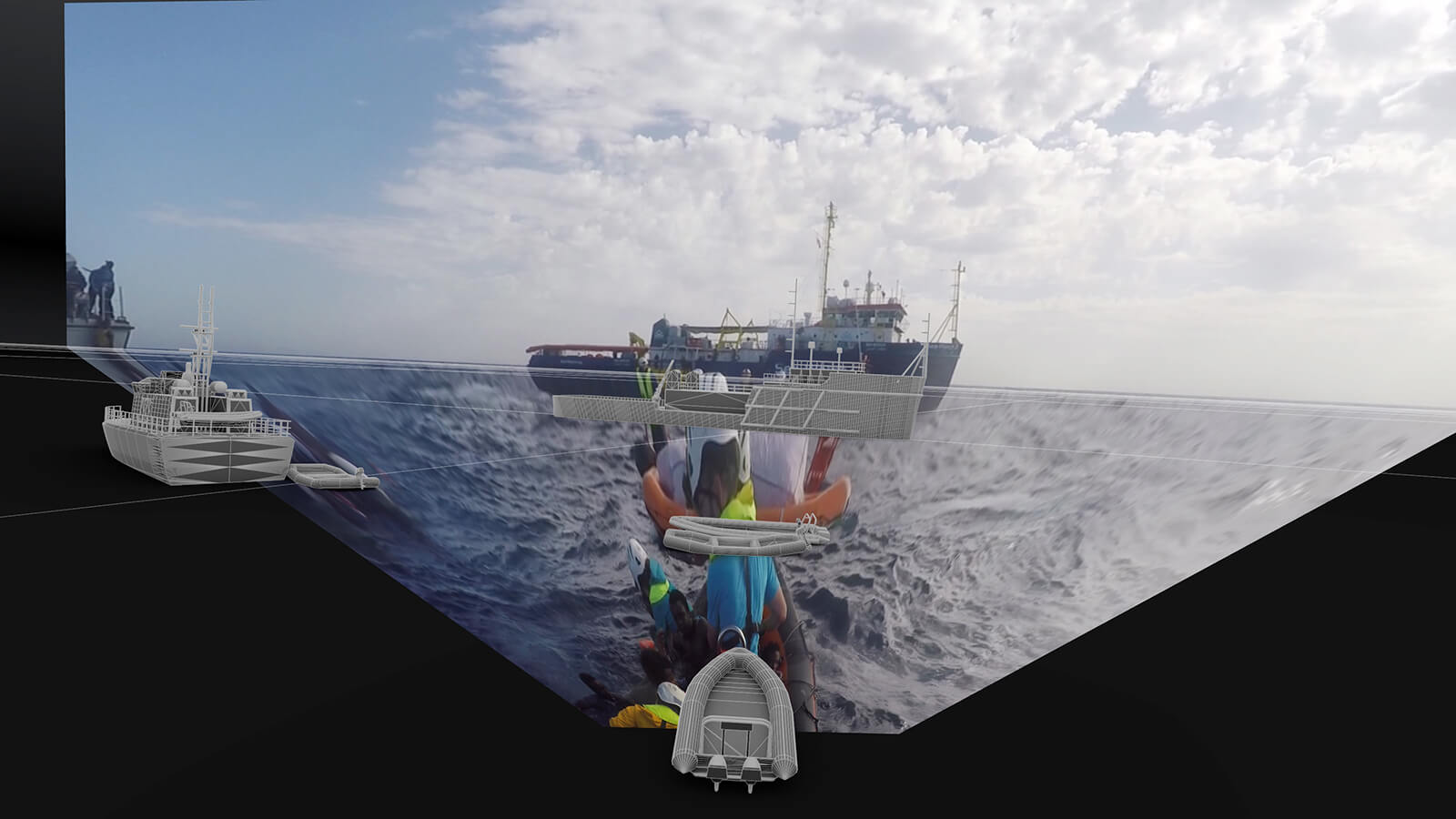

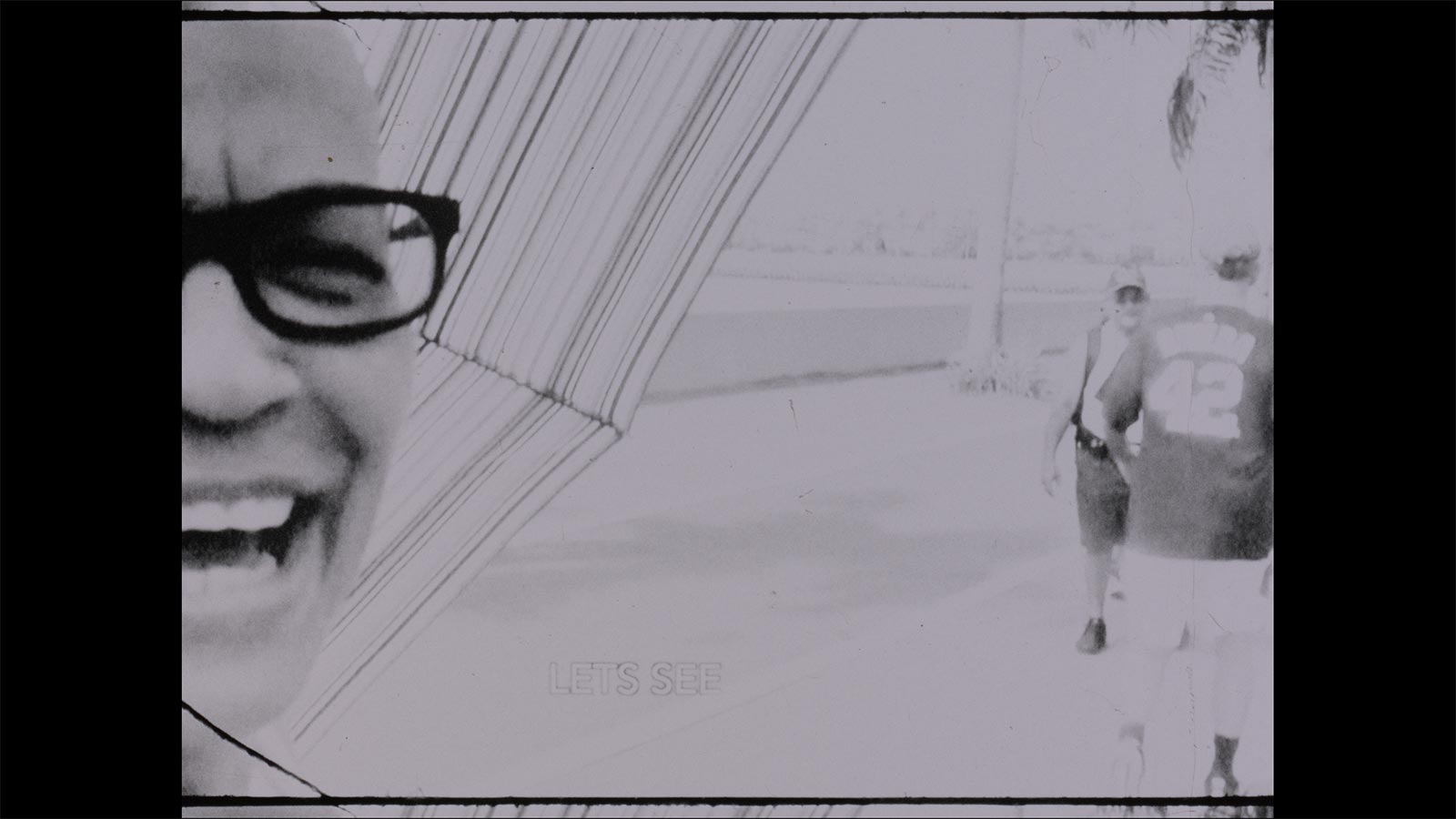

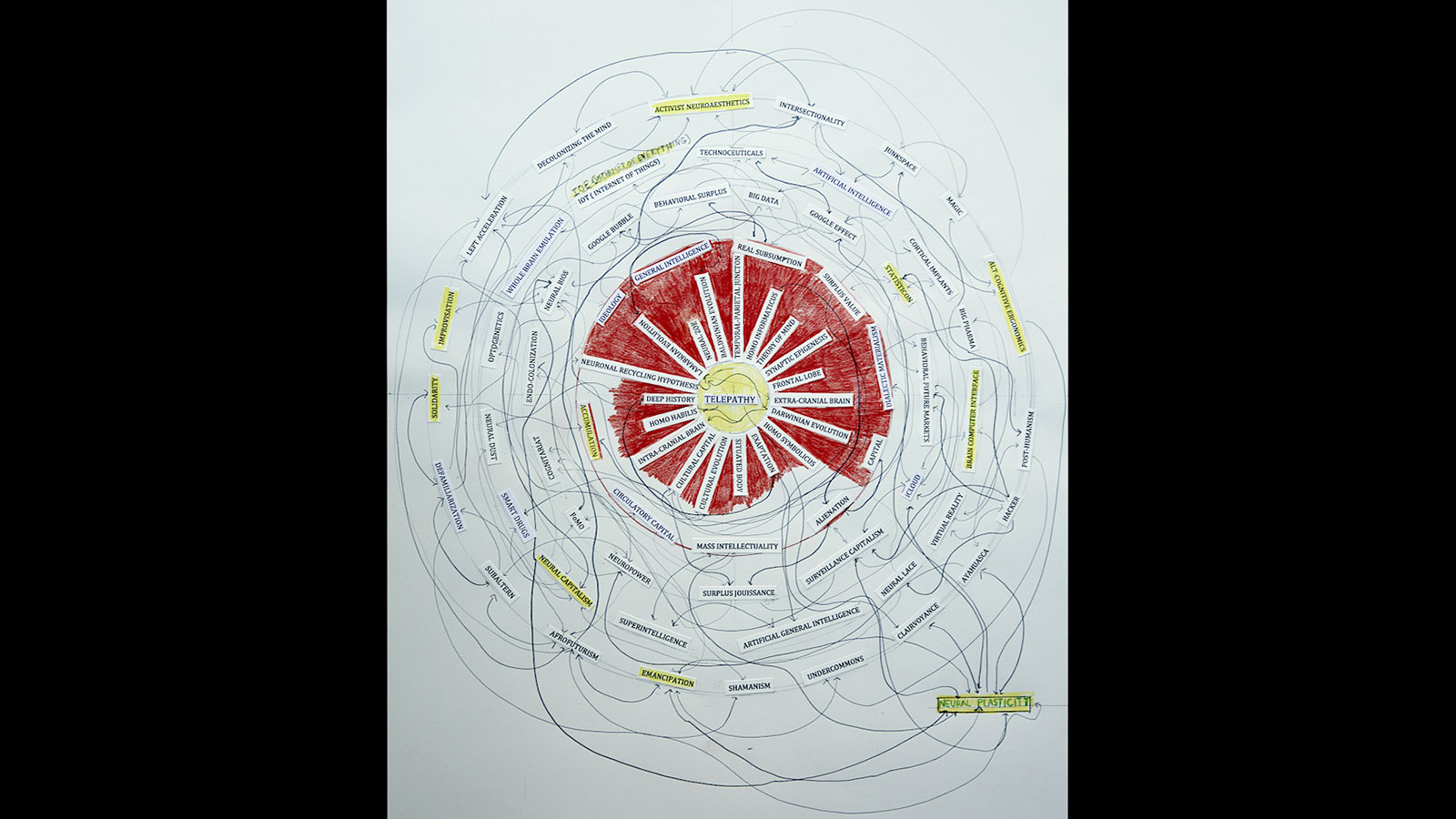

How can technologies of measurement and data analysis in art be used politically and made operative for the public sector (Forensic Architecture, “The Murder of Halit Yozgat,” 2017; Omer Fast, “A Place Which Is Ripe” and “Karla,” 2020; etc.)? In what way do they engage in the negotiation, in the rejection or defense of such categories as knowledge, truth or faith (James N. Kienitz Wilkins, “This Action Lies,” 2018; Warren Neidich, “Pizzagate: From Rumor to Delusion,” 2016–2019; etc.)? How can they subversively interact with the history of the “mismeasure of man” by repeating historical strategies of the legitimization of racist and colonialist views in compliance with media technological standards (Dani Gal, “White City,” 2018; etc.)? In which non-artistic practices of measurement, of the production of knowledge and evidence in the interest of useful research, is the use of formats involved (Thomas Julier, “Chameleon Eyes,” 2020; etc.)? In what way can artistic practice be used not only to make these involvements visible but to challenge and test them (Harun Farocki, “Images of the World and Inscription of War,” 1988; Clemens von Wedemeyer, “Transformation Scenario,” 2018; etc.)?

How can technologies of measurement and data analysis in art be used politically and made operative for the public sector? In which non-artistic practices of measurement, of the production of knowledge and evidence in the interest of useful research, is the use of formats involved? How can formats themselves, as the measures of art, be exhibited?

How can formats themselves, as the measures of art, be exhibited? In which sense can they become the “connective tissue” that relates spaces, bodies, experiences and memories (Alexandra Navratil, “Under Saturn (Act 1–3),” 2018; Alexandra Gelis, “Doing and Undoing: Poems from Within,” 2019; etc.)? How can they be put in relation to the exhibition spaces of museums and movie theaters in an institutionally critical way, and how can this relationship be assessed (Philipp Fleischmann, from “Main Hall,” 2013, to “Austrian Pavilion,” 2019; Jean-Luc Godard, “Le Livre d’image,” 2018–; etc.)? What challenges and possibilities arise regarding the historical change of formats and the practices of reformatting in artistic and curatorial practice (Marijke van Warmerdam, “Passing,” 1992; Hannes Rickli, “Videogramme,” 2005/2009; etc.)? And what kind of power over formatting must be given to film and art institutions, to their respective infrastructures and mechanisms of valorization and publicity?

We would like to warmly thank all participants for their contributions to the symposium. The videos exhibited in this online gallery are not only explorations of the topic outlined here, but also documents of a creative exchange between people who, due to the pandemic, could not meet in person as originally planned. Out of this unfortunate situation, remarkable efforts to find alternative ways of individual and collaborative contribution have been made.

The video symposium is hosted by Fabienne Liptay, Laura Walde and Carla Gabrí (University of Zurich) in cooperation with Nurja Ritter and Nadia Schneider Willen (Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst). It is funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) as part of the project Exhibiting Film: Challenges of Format.

We hope you enjoy watching the videos.

Please send questions and comments to:

exhibitingfilm@fiwi.uzh.ch